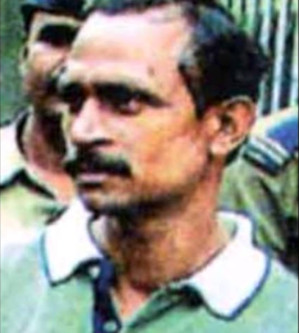

The sprawling slum of Kasturba Nagar, found within the central Indian city of Nagpur, was overshadowed by a problematic presence known as Bharat Kalicharan, or Akku Yadav, who instilled fear throughout the neighbourhood for over a decade.

His life, filled with crime and terror, ultimately culminated in a brutal end, as hundreds of women from the very society he terrorized took the law into their own hands, delivering a harsh and final judgment.

ALSO READ: Ohio cop charged in fatal shooting of unarmed pregnant Black woman accused of shoplifting

A Life of Crime

Akku Yadav, who grew up in the Kasturba Nagar slum, was the son of a milkman. However, his life turned dark as he transitioned from being a small-time thug to becoming one of the most feared gangsters in the region.

According to author Swati Mehta, Akku was a “child of the neighbourhood” who evolved into a “local menace.”

As he rose to power, Yadav ruled over a gang that dominated the slum, committing crimes with impunity. His criminal activities included penetrative sexual assault, murder, extortion, home invasion, and intimidation, leaving a trail of victims in his wake.

Akku’s earliest recorded crime was a gang ravishment in 1991, marking the beginning of a 13-year reign of terror. Throughout this period, he and his gang members ravished, tortured, and killed countless individuals.

According to Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, authors of Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, Yadav became a deplorable figure, turning his small-time thug persona into a feared mobster and kingpin of the slum. His primary method of control was extortion, and he would not hesitate to resort to violence if his demands were not met.

Yadav’s victims were often Dalit women, who, as per reports, faced immense challenges in seeking justice for the atrocities committed against them.

The brutality of Yadav’s crimes cannot be overstated. He allegedly ravished over 40 women, with his youngest victim being just 10 years old.

His crimes were not limited to sexual assault; he was also responsible for multiple murders, including that of Asha Bai, whom he killed in front of her teenage granddaughter.

Yadav’s reign was so terrifying that many residents of Kasturba Nagar compared him to the infamous fictional character Gabbar Singh, with one person noting, “We stayed mostly indoors when Akku was around.”

Despite the numerous complaints filed against him, Yadav managed to evade justice for years by bribing the local police, who not only turned a blind eye to his crimes but also protected him.

This blatant corruption left the residents of Kasturba Nagar feeling helpless and abandoned by the very authorities who were supposed to protect them.

The Spark of Resistance

The turning point in Akku Yadav’s reign of terror came when a woman named Usha Narayane decided to stand up against him.

After Yadav’s gang threatened a neighbour, Narayane took matters into her own hands, filing a police complaint against him.

Enraged by her defiance, Yadav and his gang surrounded her house, threatening to attack her with acid.

However, Narayane bravely stood her ground, threatening to blow up the house with a gas cylinder if they attempted to break in.

Her courage inspired the residents of Kasturba Nagar, who had long lived in fear of Yadav and his gang. This act of defiance marked the beginning of the end for Yadav.

Fueled by years of pent-up anger and frustration, the residents rallied together and took to the streets.

On 6 August 2004, they burned down Yadav’s house, forcing him to seek protection from the police. Ironically, the police, who had once shielded him, now arrested him for his own safety.

A Brutal End

Akku Yadav’s fate was sealed when news spread that he was to be released on bail.

On 13 August 2004, hundreds of women from Kasturba Nagar marched to the Nagpur District Court, determined to prevent Yadav from escaping justice.

Armed with vegetable knives and chilli powder, the women stormed the courtroom where Yadav was to appear.

As Yadav entered the courtroom, he brazenly mocked one of his victims, calling her a prostitute and threatening to ravish her again. This act of arrogance proved to be his undoing.

The woman, enraged by his words, struck him on the head with her footwear, signalling the beginning of a frenzied attack by the mob.

The women, many of whom had suffered at Yadav’s hands, took turns stabbing him, throwing chilli powder in his face, and stoning him.

Yadav, once a feared figure, was now pleading for his life, but the women were relentless. In just 15 minutes, Yadav was dead, his blood staining the marble floor of the courtroom.

The Aftermath

The women of Kasturba Nagar returned to their slum as heroes, having finally rid their community of the man who had terrorized them for years.

The slum erupted in celebration, with families dancing in the streets and distributing food to mark the end of Yadav’s reign. However, the legal system still had to respond to the lynching.

Several women were arrested, including Usha Narayane, but public support for them was overwhelming.

According to reports, crowds of over 400 women and 100 men gathered at the courthouse to demand their release, refusing to leave until bail was granted.

Over time, the charges against Narayane and the other women were dropped due to a lack of evidence, and they were eventually acquitted.

In an interview, retired high court judge Bhau Vahane defended the women’s actions, stating that they had been left with no alternative but to take the law into their own hands, given the failure of the police to protect them.

The story of Akku Yadav serves as a warning about the outcomes of unrestrained authority and dishonesty.

It also highlights the desperation of those who, after years of being ignored by the justice system, felt compelled to take matters into their own hands.

The tale of Akku Yadav and the women of Kasturba Nagar has been immortalized in films and documentaries, including 200: Halla Ho and Indian Predator: Murder in a Courtroom, ensuring that this chapter of vigilante justice is not forgotten.

The women of Kasturba Nagar may have acted outside the law. Still, their actions were driven by a deep-seated need for justice – a justice that had long been denied to them.

Call rape what it is – not “ravishing,” not “group ravishment.” Rape. Gang rape. This isn’t TikTok and using alternate words like that in a news article really undermines both the veracity and seriousness of the story as well as minimizes what his victims went through.

He raped and terrorized countless women and they finally received justice through his death.