Aruna Shanbaug, an Indian nurse, spent 41 years in a vegetative state after a brutal sexual assault in 1973 left her with fatal injuries.

The tragic case of Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug not only highlighted the brutal realities of sexual violence but also stirred a necessary sermon on euthanasia in India.

Aruna Shanbaug, a nurse who spent over 41 years in a vegetative state following a sexual assault, became the focal point of a legal and ethical debate that pinnacled in a landmark Supreme Court judgment on passive euthanasia.

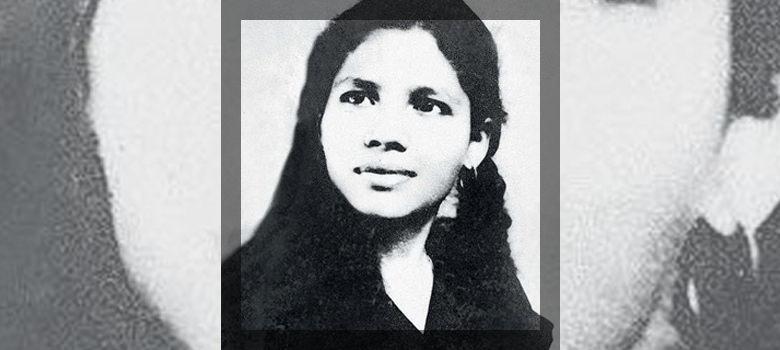

Born on June 1, 1948, in a Konkani Brahmin family in Haldipur, Uttar Kannada, Karnataka, Aruna Shanbaug was known for her dedication and compassion.

She worked as a nurse at the King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital in Mumbai, where she was highly heeded by her colleagues and patients.

At the time of the assault, she was engaged to a doctor working at the same hospital, and her future appeared bright and promising.

However, on November 27, 1973, Aruna’s life took a devastating turn.

While changing clothes in the hospital basement, she was attacked by Sohanlal Bhartha Valmiki, a contract sweeper at the hospital.

He choked her with a dog chain and sexually assaulted her.

The brutal attack cut off the oxygen supply to her brain, resulting in severe brain stem contusion, cervical cord injury, and cortical blindness.

Aruna was found unconscious the following morning by a cleaner. The assault left her in a permanent vegetative state, a condition in which she remained until she died in 2015.

Sohanlal Bhartha Valmiki was charged and convicted of assault and robbery. He served two concurrent seven-year sentences but was acquitted of penetrative sexual assault, sexual molestation, or unnatural sexual offence, charges that could have led to a life sentence.

Sohanlal was discharged from prison in 1980 and evaded further legal consequences for his actions.

Journalist and human rights activist Pinki Virani tried to track him down, believing he had changed his name and continued to work in a hospital in Delhi. However, her search failed.

Reports later suggested he had died of AIDS or tuberculosis. Still, a journalist eventually tracked him to his village in western Uttar Pradesh, where he lived with his family and worked as a labourer and cleaner.

The Supreme Court Case

In 2010, Pinki Virani, who had been a staunch advocate for Aruna’s right to die with dignity, filed a petition for euthanasia on Aruna’s behalf.

The Supreme Court of India, recognising the complexity and significance of the case, sought a report on Aruna’s medical condition from KEM Hospital and the government of Maharashtra.

On January 24, 2011, the Supreme Court set up a three-member medical panel to examine Aruna. The panel’s report concluded that she met most of the criteria for being in a permanent vegetative state.

After that, on March 7, 2011, the Supreme Court issued a landmark judgment that allowed passive euthanasia under rigid guidelines. This decision was a monumental shift in Indian law, which had previously not recognised euthanasia in any form.

The Supreme Court’s judgment laid down detailed guidelines for passive euthanasia, which involved the withdrawal of treatment, nutrition, or water.

The court stipulated that the decision to quit life support must be taken by the patient’s parents, spouse, or other close relatives. A “next friend” could decide without such relatives, subject to court approval.

In Aruna’s case, the court recognised the KEM hospital staff as her “next friend,” rejecting Pinki Virani’s petition.

The hospital staff, who had been caring for Aruna for 38 years, wished to continue her life support. The court’s decision was celebrated by the hospital staff, who saw it as a validation of their tireless devotion to Aruna’s care.

Public Reaction

The nursing staff at KEM Hospital, who had opposed the euthanasia petition, lauded the Supreme Court’s judgment.

They had been caring for Aruna as one would care for a child, with immense love and dedication. They distributed sweets and cut a cake to mark what they termed her “rebirth.”

The staff’s profound emotional bond with Aruna was evident in their response, and their efforts underscored the compassionate side of the healthcare profession.

Although disappointed by the court’s decision to reject her plea, Pinki Virani chose not to file an appeal. She hoped the case would prevent others from suffering as Aruna had.

The judgment was seen as a noteworthy step towards recognising the rights of patients in a permanent vegetative state and their families’ role in end-of-life decisions.

The Aruna Shanbaug case had far-reaching implications for Indian law and society.

The Supreme Court’s guidelines on passive euthanasia were a significant development in the country’s legal and medical landscape. These guidelines provided a framework for making difficult life-support decisions, balancing ethical concerns with legal requirements.

The case also flashed a more comprehensive discussion about the rights of patients in vegetative states and the need for compassionate end-of-life care.

It emphasised the importance of having explicit legal provisions to address such situations. It ensured that the decision-making process involved both medical experts and the judiciary.

Aruna Shanbaug’s story has been the subject of several cultural and literary works.

Pinki Virani’s non-fiction book “Aruna’s Story” (1998) provided a detailed account of her life and the legal battle for euthanasia.

RELATED: What you need to know about the Sandeshkhali land-grabbing and sexual harassment scandal

RELATED: The Story of Sajal Barui: Teen Who Killed Entire Family, Partied in Jail, and Is Now a Free Man

The Marathi play “Katha Arunachi” by Duttakumar Desai, staged in 2002, and the Malayalam film “Maram Peyyumbol” (2014), in which Anumol played Aruna, also brought her story to a broader audience. These works have raised awareness about her case and its broader issues.